HISTORICAL NOTES & EXTRACTS

Please be aware that some specialist imagery may take time to load.

This site is for dedicated researchers and is best viewed on desk or laptop.

See also: ......BIBLIOGRAPHY - RECOMMENDED READING

VINTAGE CATALOGUES ...... - ......ARTICLES & DOCUMENTS

THIS PARTICULAR PAGE CARRIES THE FOLLOWING EXCERPTS

.

Excerpt from "Modern Rifle Shooting in Peace, War and Sport" - by L.R. Tippins 1906

Excerpt on Target-shooting Groups & Group Diagnosis by W.H. Fuller from his book "Small-bore target Shooting" - 1963

Excerpt on - Instruction on Miniature Ranges - from The Imperial Army Series - Musketry Manual 1915Extract from "Rifle & Carton" - by Ernest Robinson (1914), on Rapid Shooting.

Article from target Sports "Old but still favourite" - by Chris Smith - 2001

Excerpt from The Book of the .22 - by Richard Arnold 1962 - HISTORICAL OUTLINE

Excerpt from "Rifle Shooting" by P. Fargher of the Melbourne Rifle Club - ca. 1908-14.

Excerpt on "Miniature Rifles" from "Modern Sporting Gunnery" by Henry Sharp - 1906.

Excerpt on Miniature Rifle Ammunition - Military specification .22-inch Mk.1 (from the Textbook of Smallarms 1929)

Excerpt from Modern Rifle Shooting - by L.R. TIPPINS - 1906 - Miniature Practice

Excerpt from Rifles and Ammunition- by Ommundsen and Robinson - 1915

Excerpt from Random Writings on Rifle Shooting - by A.G. Banks (1934) referring to competitions held in 1908.

Article from "The Rifleman" Offhand - by A.G. Banks - submitted Summer 1946 - advice for the Standing competitor (BEST on BROADBAND )

Interview from "The Rifleman" 'Scope Sights on .22 and Value of Marksmanship - with Brigadier-General Merritt Edson

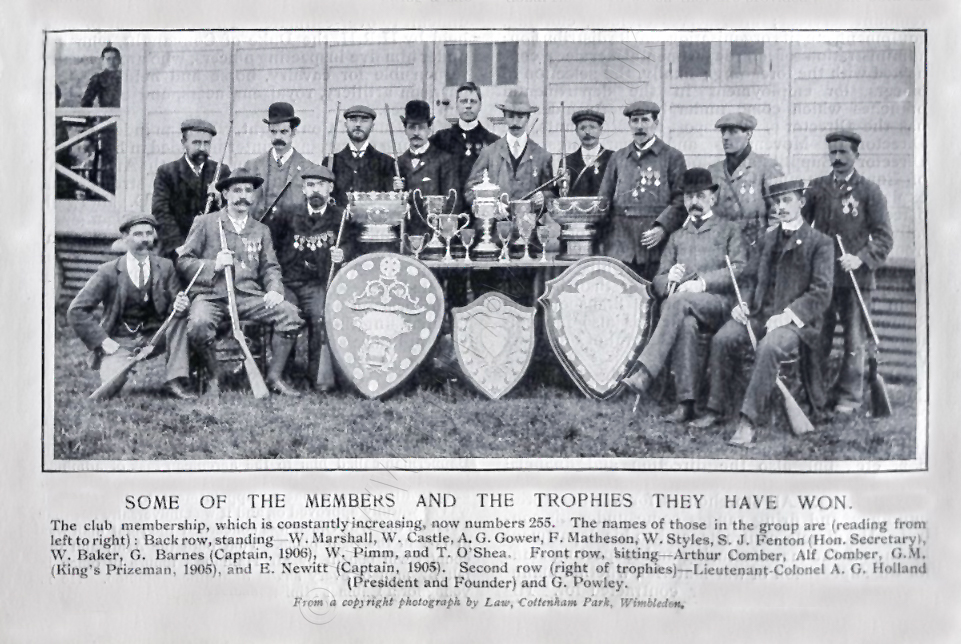

Article Champions of Civilian Marksmanship - by Philip Bourjaily on the origins of the British miniature rifle clubs

Written for "The Rifleman" - Journal of the Society of Miniature Rifle Clubs - "The Parable of Boy Jones" - by Ruyard Kipling - 1910

Extract from Encyclopædia Britannica relating to the Morris Tube, miniature rifles and rifle clubs - 1911

A tale relating a trip To Bisley with a Blunderbuss - 1999 - anon

A second extract, from " Random Writings on Rifle Shooting" by A.G. Banks, relates many aspects of small-bore shooting in the early years of the Society of Miniature Rifle Clubs. It also gives a fascinating insight into the first and second years in which the "Queen's Cup" ( Queen Alexandra Cup) competition was held.

"Questions Answered about Rifle Shooting" by BRIG. GEN. A. F. U. GREEN, C.M.G., D.S.O ., 1945

"A Few Hints on Rifle Shooting" - pamphlet by the Society of Miniature Rifle Clubs ca 1945

Excerpt from - The Imperial Army Series - Musketry Manual 1915

INSTRUCTION ON MINIATURE RANGES - INCLUDING RANGE FIELD PRACTICES Section 70 - General Remarks.1. Instruction on Miniature Ranges.--(i) Instruction on miniature ranges is in no sense a final training, but it is a useful and economical preparation for service shooting--especially useful where range accommodation is distant or altogether lacking. It should be commenced during.the recruit's training, when frequent visits should be made to the miniature range, and the lessons of aiming, pressing the trigger, declaring the point of aim on discharge, etc., should be illustrated practically by firing at elementary targets .

(ii) Object of Instruction.-Instruction should be carried out on the same principles as on open ranges. It should be progressive, and may with advantage precede instruction on open ranges. Instruction and firing may be carried out throughout the year; but if this work on miniature ranges is done during the winter months it will prove a useful preparation for subsequent practice on open ranges and for held training in the spring and summer months (see Drill and Field Training of this series, Sec. 29, para. I).

2. Scope of Training.--The instruction, which may be carried out with the Solano target and Landscape targets is more or less identical in scope with that which can be carried out on open ranges. It must be remembered, however, that the effects of varying light, wind, and other atmospheric influences are absent on miniature ranges, that instruction in judging distance is not possible. [see Sec. 72, para. 2 (iii)], that firing with sights adjusted for different ranges can only be carried out to a limited extent, and that the general conditions under which training takes place are artificial and easier as compared with training on open ranges.

3. Rifles. - The rifles used should be service pattern, .22-inch R.F., or aiming or Morris tubes used in service rifles with regulation sights. Service rifles must be used, so that the firer may become accustomed to the weight, length, bolt action, and sighting of the weapon he will use in war. Unless this principle is adhered to, practice on miniature ranges cannot be regarded as satisfactory preparation for service shooting. Rifles must be " harmonised " both for firing at targets direct or with elevation in landscape practices according to the directions laid down in Appendix, V. Rifles must also be cleaned after every ten to fifteen rounds, otherwise they become inaccurate.

4. Windgauge. - The windgauge may be used to represent wind, and the firers taught to aim off so as to correct the deflection given, acting sometimes on their own judgment, sometimes according to orders for fire direction.

5. Cover.--Cover of various kinds can be improvised at the firing-point with sandbags, screens, or other available material.

6. Empty Cases. - Empty cartridge-cases and lead should be collected, and may be sold at market rates.

7. Precautions. - (i) As the .22 cartridge used on miniature ranges has considerable power, every precaution must be taken to insure safety. Rifles must be laid down at the firing-point unloaded and with the breech-action open, and firers must stand clear whenever it is necessary for anyone to be in front of the firing-point.

(ii) A non-commissioned officer will be placed in charge of each range, and will attend whenever any practice takes place. Firing will take place only during the hours fixed by the commanding officer.

(iii) No person, except the officer or non-commissioned officer in charge, or the marker, is to pass from the firing-point up to the target during practice. Should it be necessary to stop firing, the same precautions are to be taken as at rifle practice.

(iv) Every possible precaution must be taken to avoid accidents, the strictest order and discipline being maintained at the firing-point When practice takes place on a classification range, the same orders for safety, etc., are to be observed as when service ammunition is used.

(v) In practices combining firing and movement, the non-commissioned officer in charge of the range will examine the rifles to see that they are not loaded before movement is commenced.

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

Excerpt from "Modern Rifle Shooting in Peace, War and Sport" - by L.R. Tippins 1906

THE simplest and best way to learn to use the Service rifle is to follow up the practice of position, aiming and let off by a systematic course of miniature practice. It is not possible to describe in this book all the methods nor all the details of miniature practice. The writer has done this with practical completeness in his book, "Miniature Rifle Shooting." But a short sketch of the chief methods will be given here, because there is no sort of doubt that miniature practice is real economy of time and money and a great help to real efficiency.

The cheapest form of miniature practice is with an air rifle. There are many patterns, but the best is the B.S.A. rifle, costing 50s. It is about capable of hitting an inch bull at 20 yards, and call be had with various patterns of sights. It can be obtained with stock adapted for prone shooting, but the ordinary form is adapted for standing only. Riflemen should, of course, buy that which can be used prone. Slugs cost 1s. 6d. per thousand. The use of such a weapon is proved to be of considerable value to beginners, and competition with it is amusing and instructive, and forms a good addition to the attractions of drill. Twelve yards is quite sufficient range for air gun work, but for all other miniature practice 25 yards is the best range. Many air-guns are smooth bore, and no use to riflemen.

Practice with miniature rifles is also useful, but its value depends a good deal on the type of rifle and of the sights. The cheapest cartridge to use is the .22 rim-fire short, and it is very accurate up to 25 yards, and costs little more than a shilling per 100. It is a mistake to use rifles for miniature work which use cartridges costing four or five shillings per 100, and yet not more accurate at miniature distances than the .22.

But whatever rifle is used, the sights on it should be open, not aperture. For the use of aperture sights is almost no training for open sights, and is a waste of time to a man who wishes to learn to use any Service rifle. But many miniature rifles are too small for men, and do not allow of the use of the sling.

The rifleman learning to use the Service rifle, or desirous of more practice with it, will find several methods open to him. The best and cheapest in use is the use of a regulation pattern rifle fitted with a .22 barrel. Such a rifle costs, new, five guineas, but an old rifle can be converted for 55s. The bolt head and the striker are modified, but the rest is exactly the Service pattern. The short cartridge is good enough for 25 yards, but the "long rifle" .22 cartridge ran be used up to 100 yards.

A similar rifle taking the 297/230, or "Morris" cartridge, costs the same price new, and slightly less for conversion. The cartridges, however cost about twice as much as the .22's, and are certainly not more accurate, and as issued by Government are much less accurate. But the long 297/230 can, be used fairly well at 200 yards especially some of the smokeless loads.

The actual Service rifle can be used for miniature practice by the insertion of a tube in the barrel, so that it takes a small cartridge, This is the "Morris Tube" invented about 1881 by Colonel Morris. Tubes are sold to take the 297/230 cartridge, and also others to take the .22 cartridge, but the same tube will not take both. The tube for .22 can only be used after modifications of the bolt, but is cheaper in use. the tube alone costs 25s. and the 297/230 cartridges from 2s. to 2s.9d. per 100.

A rival method of using the Service rifle is by means of a "chamber bush", or "adapter," which fills up the greater part of the rifle chamber, so allowing a short small cartridge be fired. The bullet, however, fits the bore, and follows the grooves in the actual barrel. There are several forms of adapter, but the differences are of no great importance. The cartridges cost about 4s. per 100, and the adapters about 4s.6d. each. They are very little use beyond 25 yards.

There are two systems of practice which use cases of the regulation size. Gaudet's reloads are fired cases crimped and loaded with a small charge of black, or of bulk smokeless powder and usually a nickel-based bullet. They can be fired but once. They cost 40s. per 1,ooo, and shoot well at 100 yards. Trask's reloads consist of a steel case outwardly the same size as the regulation cartridge. The powder charge is inserted in the base of this case from the breech in the form of a blank cartridge, and the bullet is put in the front end of the steel case. Reloading is simple and quickly done, with no chance of serious error. The shooting is good at 100 yards, and the cost is 15s. per 1,ooo for reloads and 6d. for the steel case.

Ordinary fired cases can be reloaded with small charges for miniature work, but special tools are needed, and the job has risks in the hands of the inexperienced. It has charms of its own, and is instructive in various ways. The cost, apart from the labour, is from 20s. to 30s per 1,000. At 25 yards a degree on the vernier with leaf up makes a quarter inch difference on the target; at 20 yards a degree makes 1-5th of an inch difference. Many men find it quite possible to set up a little miniature range of their own for practice. The essentials are simply space, light, and a stop for the bullets. Though it is an offence at law to fire within 50 feet of the centre of a road, the target itself may be nearer the road. If noise is a nuisance to neighbours, it can be greatly minimised by the use of the smokeless brands of .22 short cartridges and a soft stop for the bullets, such as a bag of hay or sawdust, or malt culms. But the stop must be efficient and kept efficient.

The targets should be card copies of the Bisley targets reduced to scale for the distance used. They can now be bought very cheaply, or made at home. The "500 yards" target should be raised up some 6 inches or so above the target aimed at, and the sight raised so that the bullets strike it. The 600 can be raised a bit higher.

The great drawback to miniature practice is that it may be carried out in lazy fashion, and so teach bad habits. This will be avoided by men who are really determined to make the most of their life; but often the introduction of the element of competition keeps men keen. At drill halls especially, competitions are of great use, and help recruits as well as old hands. Certainly, miniature practice is of much more value to Volunteers, and even to Regulars, than eternal drudgery at the same old manual, or even squad drill. Volunteers can hardly be expected to appreciate continued practice of movements which are of not the slightest value in war, and in striving for uniformity which is no use when obtained. Miniature work at moving targets has considerable value, but details cannot be given here.

In the Army a saving of tens of thousands of pounds every year, and practical doubling of efficiency could be obtained, by revision and improvement of the methods and appliances for miniature work.

There is an incidental gain in miniature practice at home, in that it does not take a man away from his home, and can often be shared by his family, especially the boys. It is good for the boys to learn with and from their father, and he will often have to hurry up to keep ahead of them. One real difficulty in Volunteer work is that it takes a man so much away from home-life, even in the time of respite from work. Miniature work reduces the time necessarily spent on the range, and especially in getting to and returning from it

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

We here include this extract from a chapter of "Rifle & Carton" by Ernest Robinson (1914), on Rapid Shooting. This is not intended to make any adjustment to our present League rules, which are unified to limit differences between classes and disciplines. The content is still relevant, and the piece could easily have been written yesterday! MANY a man who can shoot well deliberately comes to grief when he has to shoot a rapid. As most of the important miniature aggregates contain a rapid shoot it follows that the good rapid shots are the men whose names are usually to he found at the top of the Iist. Almost all the rapid shooting is done at the green secondary target, and the time limit is 90 seconds. The time allowance is ample, but most men find the target a difficult one in all but the very best light.

A young shot just starting to visit the open meetings is painfully aware of the difficulty of the " 10 shots in 90 seconds on the secondary target at 50 yards " that figure in all the S.M.R.C. championship shoots, and he is also alive to the necessity of scoring well on it. As a consequence, he probably does a deal worse than there is any necessity for. He may be told that there is no necessity to practise the rapid shooting and that no amount of practice will assure him of a good shoot. This may be true, but practice is always useful, and a good deal of practice will tell the aspiring marksman exactly how much time he can afford to spend over the aim. The S.M.R.C. Rules require the cartridge to be in the fingers and the butt off the shoulder until the word " get ready." The rifleman is given time to get into a perfectly comfortable position before the warning command is given, and he will find it most expedient to be waiting with the cartridge just resting in the breech. At the command "get ready`" the cartridge is pushed home and the breech closed, in a flash the butt comes to the shoulder with the same movement, and the aim should be ready and steady when the command " commence " comes three seconds later. (Not for you! - Ed)

The art of rapid shooting consists in taking as little time as possible in loading and all this is required in aiming. In S.M.R.C. competitions it is usual to call out every ten seconds so that the marksman has an absolute knowledge of the time he has to spare. If the first shot is got off steadily at the word "commence," as it very well can be, then one shot each succeeding 10 seconds will leave ten seconds to spare.The great "tip" is to keep position all through the shoot, particularly with the left elbow and the body. If these do not move the right elbow can be left to take care of itself.

The sight described in the article on foresights, a broad blade, is the best in the writer's opinion for rapid shooting, as it allows the object to be picked up with certainty. A three-bladed sight might perhaps be better, but nothing that blocks out much of the field of vision is advisable for rapid shooting. Everything that wastes time should be eliminated in a rapid shoot, and any uncertainty in picking up the object is fatal to good shooting. Rapid shooting at the green target at 100 yards is exciting sport, and a fine test of rifle, ammunition and man. At this range at the secondary target anything over 95 is very good. There are, of course, men who can put on 98's and 99's but they are very lucky if they get them in open competitions.

A good "98" made in 90 seconds on the old time-limit target.

Spotting is usually forbidden in rapid shooting, so that it pays a man to know the exact elevation and direction zero for the foresight he is using. Most men have a tendency to shoot "right" rapid on the green target, partly due, no doubt, to "pulling" because of the speed. In making the change from the ring foresight to the broad blade, if the rifleman does it, he must not forget to make the necessary corrections on his back sight. If he is shooting where he is not allowed sighting shots he will have to take an unlimited ticket, or perhaps two, before he has got his sighting right. At 25 yards there are three figures on the secondary target. It is a good plan to put four shots on the middle one. Not less than three shots must be on any of the figures. It pays to aim at the object always. Keep cool and keep steady, don't lose position, load "like greased lightning," and remember there is time enough for a just aim even when all the shots have to go in 90 seconds. It is better for your score to take 85 seconds than 75. Nothing is gained by hurrying.

Many of the best rapid shots seem to get a regular rhythm into their movements like the beat of a pendulum They will be found to take the same amount of time almost to a second for each series of ten shots. Rapid shooting requires some knack, and the knack comes with experience and practice.

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

target Sports article "Old but still favourite" by Chris Smith - 2001

Historic .22''s at the Essex County Championships.If you live and shoot in Essex you will know perfectly well that all smallbore shooting is not prone - unlimited sighters and twenty to count, wearing a jacket that would do very nicely in a bondage movie and pumping enough iron (and wood) to satisfy an Arnold Schwarzenegger. Why, because if you had gone to the Essex County Smallbore Championships at Basildon (13 May 2001) you would have seen the first class array of classic and historic .22 rifles put together by members of the NRA's Historic Arms Resource Centre.

They, and other members of the Royal British Legion Mersea Island Rifle Club for whom the occasion was an open day, brought out their collections to both show and shoot. A constant stream of visiting shooters took time out of their normal pumpin' iron target shooting to have a go with any of over eighty .22" rifles on show.

There were prone and standing events for the standard classic competitions and classes: Veteran, Classic, and Service; these were deliberate 50 yard prone shoots. In addition, there were standing classes for pump action and self-loading, any sights, including contemporary telescopic sights, shot against the clock - two series of 5 shots in 20 seconds for pump or manual action and 10 seconds for semi-auto .22 rifles, as well as a deliberate target rifle class. The great plus to this was the six-foot wide landscape target.

For those who've never seen one, the landscape target is a good six feet wide showing a battle ground scene as a soldier of the first half of the 20th century would have recognised. One does not shoot such a work of art to pieces however. Rather, there is a blank white target above the painted battlefield scene and it is on this that shots and groups are recorded. To shoot this, one ideally uses a No.7 or No.8 rifle with the 'H' marked harmonisation sight. By setting your sights on 'H' to shoot on this 25 yard target, one's shots - aimed at a particular strong-point or barbed wire entanglement on the battlefield, strike the plain sheet 27" above. Using the target converter - a 27" pointer with scoring rings - the "target" is marked and the intended fall of shot compared with the actual shot hole above. This pairs competition excited much interest, shot as pairs I'm not altogether sure it encouraged club harmony, since many participants were not used to shooting freestyle, but did their best and enjoyed themselves no end. It is quite a sight to see a thoroughly mature and long standing traditional target shooter giggling like a youngster , at the results of their intended and recorded targets (scores ?) on this Somme like battlescene.

As with all the rifles on display, the Enfield No.7 and No.8 rifles were exhibited and loaned by members of the HARC Miniature Rifle Section.

Other rare and interesting sights - in addition to the look-alike No.4 , but in .22 (the No.7 rifle) - included a Swiss Schmidt-Rubin 1889 rifle converted to a .22 trainer in 1911 pattern, this racked next to a Russian T-1935 training rifle. The comparisons were quite stark, the beautifully engineered Swiss compared with the almost brutal simplicity of the Russian trainer. For engineering perfection, one had only to examine the Ross straight-pull in .22, a fine and really quite rare example of this type of rifle; interestingly, it had the fairly standard BSA type mid sight, which is adjusted by rotating an outer ring for elevation, in addition to the rear peep sight which could be swivelled out of the way.

In keeping with the theme of the collection, there were both Models A and B Swift training rifles. This novel rifle, designed in Czechoslovakia before WW2 was patented in the UK in 1941 and manufactured in Oxford. Never an official army issue, it was on charge with the RAF and in use for Cadet training up to the 1960's and later. Some army units did also use them and a number of Home Guard units acquired them for training. The great thing about the Swift is that you can use it anywhere, since it "fires" two captive pins, which strike a target on a frame set a fixed length from the end of the rifle. The shape and location of the round and rectangular holes punched in the target indicated whether the rifle was canted, properly aimed, held tight into the shoulder etc., mirroring the effect of a real, full-bore service rifle. No doubt ACPO would approve of this rifle.

The display covered sporting, target and military training rifles of over 100 years. A number of Martini conversions were on show, including a Martini-Metford carbine fitted with a Morris tube in .297/.230" calibre. This was next to a cut down Long Lee - officially done over 80 years before anyone started having palpitations over vandalism. They were cut down to emulate the SMLE, and fitted with a .22 barrel. To this was added a most emphatically over-engineered magazine which slotted into the standard .303 magazine and allowed the bolt to be worked in the normal manner and with pretty well normal bolt travel and movement - even to the extent of heavy springs requiring similar force to counteract as the cocking of the .303" rifle. This Hiscock-Parker magazine is a very rare item indeed. It was a real pleasure to shoot these training "Rifles .22 RFShort Mk.l and Mk.ll". Apart from the lack of bang and recoil from both these and the .22" Pattern 18, (known as the ".303-cum-.22" conveyor rifle), it felt just like handling the real thing.

There were any number of BSA Martinis, including Models 2, 4, 6, 8, 10,12, 13, 15 - including the Centurion variant and, of course, the ubiquitous 12/15 together with their Remington and Winchester counterparts. However, of interest was a prototype BSA Mk.lll International. One of only 5 made, it carried a steel forend hanger. In production, to reduce weight, the steel was replaced with aluminium, with all the subsequent problems. However, in the trials batch, steel was used, which no doubt explains its accuracy, such that this particular rifle won a whole sheaf of U.K. and European medals during 1963 including the British Championship for the "Roberts" and then made its way to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

I initially passed by a little BSA pump action until a second glance revealed the "Gnomet" 2½ x "OIGEE - BERLIN" scope fitted to it. Consequently, I just had to try it on the 50 yard sporting rifle timed shoot. The results say more than I care to recognise about my shooting, than about the scope which is now getting on for seventy years old and still shooting straight. A modern scope will no doubt have better light capturing capacity, but the clarity in decent light was quite a surprise.

Spanning the Second World War was the unusual self-loading BSA Ralock rifle, which loaded through the butt and, being a tidy sort of rifle, retained all the empty cases in the mechanism until emptied by the shooter. Initially designed just before the war, it was brought into production after 1946, lasting only a few years. Generally rather over-engineered, it was a take-down rifle that threw back to the days of machined components rather than stampings, and couldn't compete with the post war generation of cheap .22 semi-autos.

I was only dimly aware that Vickers had made .22" TARGET RIFLES in the 1920s and 30s, yet here was a pretty well complete collection of this Martini style rifle, from the Mkl with the receiver mounted folding rear-sight (but also fitted with a Parker-Hale target- scope sight) along side the Specials (in different barrel and stock configurations) the, Jubilee, Empire and Champion Models. This was probably the largest collection in captivity - and there were still more that the several HARC and RBLMIRC members had not brought with them!

Underlever fans - eat your heart out. An underlever rifle that worked what was in effect a straight-pull bolt, in the very short lived Barnett design rifle of the 1950s. Very few were ever made, probably little more than 300, and this example is really in very good condition and quite smooth to operate.

I've saved the best 'til last. This was a Stevens 44½/52. A fairly standard single shot falling block action; but fitted with a heavy barrel, set triggers and engraved action, it was a really fine example of the American Schutzen discipline. I Shot standing at 50 yards, and this is not as easy as one thinks, although the weight of the rifle does help keep it steady. You can see this discipline being shot in competitions in its own right as well as at the Bisley Historic Arms meeting during the Imperial, and at the Trafalgar meeting in October. Growing in popularity, members of the HBSA are carving out quite a niche for themselves in this quite fascinating area of collecting and shooting.

Now generally speaking, I can get quite sniffy about .22" rifles and shooting - although anything which goes bang must be all right. However, I've never seen such a collection of .22" historic rifles on display, with the choice of competitions and disciplines giving me a new insight into this still relatively cheap part of our sport. With the emphasis on the enjoyment and bringing back into commission the rifles of our fathers and grandfathers, shooting and collecting historic and classic small bore rifles is a discipline open to all and should be encouraged by the Associations if shooting sports are to flourish.

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

Excerpt from THE BOOK OF THE ·22 Richard Arnold 1962 HISTORICAL OUTLINE

Alongside the development of the ·22 rifle and its ammunition there have been inventions,

some excellent, some useful, some downright impractical, relating to the · 22 as a training

arm, as an ancillary weapon, or as an accessory to it. Two remarkable developments standout: one perfected in the United States and one in Great Britain. The first, the floating chamber principle, was the invention of Marshall Williams, who devised it whilst serving a sentence in a United States penitentiary for an offence during the days of Prohibition. For sometime the American forces had been using the Colt ·45 semi-automatic pistol for training their personnel, but the cost of ammunition presented problems. The use of a ·22 pistol, built like the ·45, did not solve the problem. Smaller calibre ammunition made it more economic but without the buck of a heavy pistol in recoil, the use of a ·22 did not assist much in preparing a nervous recruit to handle the heavier handgun. Williams devised the floating chamber in which the gas produced from the fired cartridge of a ·22 was allowed to escape at the front of the chamber. This gas thrust against the area of the cartridge base plus the considerably larger area of the chamber front. The backward action of the gases was therefore considerably increased, the thrust of the weapon in recoil greater in consequence. The net result was that a ·22 pistol was built giving the same recoil as the larger ·45.

The next step was the incorporation of the floating chamber using the ·22 long rifle cartridge into the Browning machine-gun. In addition to building floating ·22 chambers for many semi-automatic rifles, Williams designed the short-stroke piston for the Garand automatic carbine, but that is outside the scope of a brief historical survey of the ·22.

Improvements have been made on the original Morris tube invention - ·22-calibre adapters have been made to insert into the barrels of shotguns, whilst Parker-Hale Ltd of Birmingham brought out a really first-class adapter for the Webley and Scott ·455 calibre service revolver. This, though it did not incorporate any floating chamber principle to increase recoil, was none the less a great aid in training the pistolmen in shooting. It was made in two patterns, as a single-shot adapter, in which the cylinder was removed from the pistol so that it was fired in skeleton form, or complete with a special cylinder chambered for the ·22 rim-fire cartridge. This adapter was also manufactured for the ·38-calibre Enfield Service Revolver

These adapters are still in use today and used fairly extensively. They do not affect the accuracy of the revolvers and are guaranteed to shoot into a 3/4 - inch group at 20 yards, which is better than the handler can claim.

The most remarkable development was, however, the principle, derived from the Morris Tube, by Mr. A. T. C. Hale in introducing the system which he called 'Parker-rifling'. In this, worn barrels are bored out and a new rifled tube is inserted. Nor is this confined to worn barrels, for many larger bores, such as ·303 service rifles, can be converted to ·22 rifles by this process. It is an economical way of making a first-class sporting arm from an obsolete military one. It is not suitable for military cartridges, nor for high-power sporting cartridges, though Parker-rifling is suitable for the ·22 Hornet. It seems strange that many a useless high-power, large-calibre weapon should become a small ·22-calibre arm capable of extremely accurate shooting, yet there it is. Commonplace the ·22 may be, yet its history is colourful and proud: whatever the future may hold in the development of firearms and ammunition, the little ·22 occupies an important position in the history of firearms as a whole. Large-bore riflemen may hold it in contempt, but most successful riflemen start with this weapon, while for military purposes its utility in training has been proved time and time again.

From the standpoint of the ordinary shooter, the ·22-calibre rifle is the most important in the world and there is a lot to be said for their attitude. Perhaps, speaking of Great Britain alone with its growing numbers of riflemen, one could parody the old song and say: 'Four thousand rifle clubs can't be wrong!'

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

MINIATURE RIFLE AMMUNITION - Mk.I Military specification (from the Textbook of Smallarms 1929) The service miniature rifle cartridge is the ·22-inch rim fire Mark I. There is however no exact design for this cartridge, and the specification governing its manufacture is worded so as to allow of small variations in construction, sufficient to admit the use of similar trade patterns. The chief requirement is accuracy, and it is essential that the cartridge should function satisfactorily in the ·22-inch service short rifle.

The term ' rim fire ' signifies a cartridge without a cap, the flange or rim of the case being hollow and filled with cap composition. In a rim fire rifle the striker is placed eccentric to the axis of the barrel, and when the rifle is fired the striker pinches the hollow rim and thus fires the charge.

The case of the Mark I cartridge is solid drawn and is usually made of copper, though the use of brass or cupro-nickel is permitted. The rim is usually primed with about 0·1 of a grain of cap composition, the ingredients of which are identical with those used in the ·303-inch Mark VII cartridge.

The bullet is made of an alloy of lead, and weighs 40 grains. Three cannelures are provided, usually lubricated with beeswax. The bullet is secured into the case by coning, indenting or crimping.

The charge may consist either of cordite, or rim neonite, or other nitrocellulose powder, the most common form of charge being about 1·2 grains of rim neonite. No wad is provided.

The accuracy of the ammunition must be such that when fired from a service ·22-inch short rifle, mounted in a fixed rest it must be capable of putting 95 per cent. of the bullets into or cutting a three quarter-inch circle at 25 yards, the rifle being cleaned not oftener than once in 60 rounds. The cartridges must also be free from hangfires: missfires, split cases and blowbacks, and must load and unload freely in the rifle. This is the only service small arm cartridge the inspection of which is carried out on a percentage basis. Although in the case of other types of small-arm ammunition, a complete inspection of every round is essential, there are reasons why in the case of the rimfire cartridge this is not so. It is practically impossible to manufacture a round which is dangerous either to the firer or to the weapon, and under these circumustances the presence of an occasional defective round is not so serious as it would be in the case of ordinary ball ammunition, since the rim fire cartridge is used exclusively for training purposes. The cost of a complete inspection would also be prohibitive.

For service purposes these cartridges are packed head and tail in cardboard boxes, each holding 100 rounds. Ten of these cardboard boxes are enclosed in a tin lining with a tear-off lid, and ten such tin linings are in turn packed in a wooden box, which thus holds 10,000 rounds. The characteristic symbol on the distinguishing label is a green target on a white ground, overprinted with the figure I in black.

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

EXCERPT FROM "MODERN RIFLE SHOOTING" by L.R. TIPPINS - 1906 - Miniature Practice THE simplest and best way to learn to use the Service rifle is to follow up the practice of position, aiming and let off by a systematic course of miniature practice. It is not possible to describe in this book all the methods nor all the details of miniature practice. The writer has done this with practical completeness in his book, "Miniature Rifle Shooting." But a short sketch of the chief methods will be given here, because there is no sort of doubt that miniature practice is real economy of time and money and a great help to real efficiency.

The cheapest form of miniature practice is with an air rifle. There are many patterns, but the best is the B.S.A. rifle, costing 50s. It is about capable of hitting an inch bull at 20 yards, and call be had with various patterns of sights. It can be obtained with stock adapted for prone shooting, but the ordinary form is adapted for standing only. Riflemen should, of course, buy that which can be used prone. Slugs cost 1s. 6d. per thousand. The use of such a weapon is proved to be of considerable value to beginners, and competition with it is amusing and instructive, and forms a good addition to the attractions

of drill. Twelve yards is quite sufficient range for air gun work, but for all other miniature practice 25 yards is the best range. Many air-guns are smooth bore, and no use to riflemen.

Practice with miniature rifles is also useful, but its value depends a good deal on the type of rifle and of the sights. The cheapest cartridge to use is the .22 rim-fire short, and it is very accurate up to 25 yards, and costs little more than a shilling per 100. It is a mistake to use rifles for miniature work which use cartridges costing four or five shillings per 100, and yet not more accurate at miniature distances than the .22.

But whatever rifle is used, the sights on it should be open, not aperture. For the use of aperture sights is almost no training for open sights, and is a waste of time to a man who wishes to learn to use any Service rifle. But many miniature rifles are too small for men, and do not allow of the use of the sling.

The rifleman learning to use the Service rifle, or desirous of more practice with it, will find several methods open to him. The best and cheapest in use is the use of a regulation pattern rifle fitted with a .22 barrel. Such a rifle costs, new, five guineas, but an old rifle can be converted for 55s. The bolt head and the striker are modified, but the rest is exactly the Service pattern. The short cartridge is good enough for 25 yards, but the "long rifle" .22 cartridge ran be used up to 100 yards.A similar rifle taking the 297/230, or "Morris" cartridge, costs the same price new, and slightly less for conversion. The cartridges, however cost about twice as much as the .22's, and are certainly not more accurate, and as issued by Government are much less accurate. But the long 297/230 can, be used fairly well at 200 yards especially some of the smokeless loads.

The actual Service rifle can be used for miniature practice by the insertion of a tube in the barrel, so that it takes a small cartridge, This is the "Morris Tube" invented about 1881 by Colonel Morris. Tubes are sold to take the 297/230 cartridge, and also others to take the .22 cartridge, but the same tube will not take both. The tube for .22 can only be used after modifications of the bolt, but is cheaper in use. the tube alone costs 25s. and the 297/230 cartridges from 2s. to 2s.9d. per 100.

A rival method of using the Service rifle is by means of a "chamber bush", or "adaptor," which fills up the greater part of the rifle chamber, so allowing a short small cartridge to he fired. The bullet, however, fits the bore, and follows the grooves in the actual barrel. There are several forms of adapter, but the differences are of no great importance. The cartridges cost about 4s. per 100, and the adapters about 4s.6d. each. They are very little use beyond 25 yards.

There are tmo systems of practice which use cases of the regulation size. Gaudet's reloads are fired cases crimped and loaded with a small charge of black, or of bulk smokeless powder and usually a nickel-based bullet. They can be fired but once. They cost 40s. per 1,ooo, and shoot well at 100 yards. Trask's reloads consist of a steel case outwardly the same size as the regulation cartridge. The powder charge is inserted in the base of this case from the breech in the form of a blank cartridge, and the bullet is put in the front end of the steel case. Reloading is simple and quickly done, with no chance of serious error. The shooting is good at 100 yards, and the cost is 15s. per 1,ooo for reloads and 6d. for the steel case.

Ordinary fired cases can be reloaded with small charges for miniature work, but special tools are needed, and the job has risks in the hands of the inexperienced. It has charms of its own, and is instructive in various ways.The cost, apart from the labour, is from 20s. to 30s per 1,000

At 25 yards a degree on the vernier with leaf up makes a quarter inch difference on the target; at 20 yards a degree makes 1-5th of an inch difference.

Many men find it quite possible to set up a little miniature range of their own for practice. The essentials are simply space, light, and a stop for the bullets. Though it is an offence at law to fire within 50 feet of the centre of a road, the target itself may be nearer the road. If noise is a nuisance to neighbours, it can be greatly minimised by the use of the smokeless brands of .22 short cartridges and a soft stop for the bullets, such as a bag of hay or sawdust, or malt culms. But the stop must be efficient and kept efficient.

The targets should be card copies of the Bisley targets reduced to scale for the distance used. They can now be bought very cheaply, or made at home.

The "500 yards" target should be raised up some 6 inches or so above thetarget aimed at, and the sight raised so that the bullets strike it. The 600 can be raised a bit higher.

The great drawback to miniature practice is that it may be carried out in lazy fashion, and so teach bad habits. This will be avoided by men who are really determined to make the most of their life; but often the introduction of the element of competition keeps men keen. At drill halls especially, competitions are of great use, and help recruits as well as old hands. Certainly, miniature practice is of much more value to Volunteers, and even to Regulars, than eternal drudgery at the same old manual, or even squad drill. Volunteers can hardly be expected to appreciate continued practice of movements which are of not the slightest value in war, and in striving for uniformity which is no use when obtained. Miniature work at moving targets has considerable value, but details cannot be given here.

In the Army a saving of tens of thousands of pounds every year, and practical doubling of efficiency could be obtained, by revision and improvement of the methods and appliances for miniature work.

There is an incidental gain in miniature practice at home, in that it does not take a man away from his home, and can often be shared by his family, especially the boys. It is good for the boys to learn with and from their father, and he will often have to hurry up to keep ahead of them. One real difficulty in Volunteer work is that it takes a man so much away from home-life, even in the time of respite from work. Miniature work reduces the time necessarily spent on the range, and especially in getting to and returning from it

SUMMARY

I. Miniature practice is the best method of learning shooting.

2. Can be carried out with

a. Air rifle.

b. Miniature rifle.

c. Service rifle, either

(1.) With small calibre barrel.

(2.) With tube in barrel.

(3·) Adapter in chamber.

(4·) Reduced loads.

3· Provides instruction and recreation for all classes of riflemen.

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

H. Ommundsen won the King's Prize at Bisley in 1901 as a Corporal. Between 1913 and 1915, as a most successful and experienced shot he wrote, in partnership with E.H. Robinson, "Rifles and Ammunition" , which was one of the most comprehensive text books of the day on rifle-shooting. Ommundsen sadly did not long survive after commencement of the First World War. The death was reported, in the London Illustrated News of September 9th. 1915, of Lieut A. N. V. H. Ommundsen, Hon. Artillery Company. He was an analytic and inventive soul, and had been responsible, in conjunction with E.J.D. Newitt, for the design of the Remington Negative-Angle Battle Sight. This design principle was patented by them in March 1911 (No.8038), and the final product design in December of that year (No.28,194). The sight permitted aiming a fixed distance below the the target, and was intended to "enlarge the danger zone under skirmishing conditions" to enhance the chance of a hit. Ommundsen's co-author of the book, Ernest Robinson (himself a King's Prize winner in 1923), later wrote a number of small training books, e.g. Rifle Training for WarExcerpt from RIFLES AND AMMUNITION by Ommundsen and Robinson - 1915

In 1902, there were already many criticisms from military men that the shooting experience gained on rifle ranges was not of the kind likely to be of value from a military point of view. Though many of the civilian rifle clubs were at that date of a semi-military character, that is to say, they indulged in drill and were taught by ex-military men, the rifles they used were extremely unlike the ordinary military pattern. Towards this, the N.R.A. rule limiting the weight to below 8 Ib. had some considerable influence, and it was only when the majority of shooters, through the Society of Miniature Rifle Clubs, brought pressure to bear on the parent association that the weight of the miniature rifle was extended so as to include any reasonable design.

But to return to the criticisms of 1901 and 1902. We have heard these criticisms many a time, and it is interesting to see how little they have varied during the passage of years. In 1901 an Army officer wrote to a morning paper saying that if the men were to be taught to handle the rifle so as to use it efficiently in time of need, they must be taught with the kind of weapon they were likely to have to use in war. Efficient use came only with familiarity, and there was no possible excuse for making each man familiar with a light and childish weapon when he would have to use one very consider-ably heavier when he came to fight.

The answer to such criticism was obviously to adapt the Service rifle to fire the reduced bore cartridge, and in February, I902, Messrs. Buck & Co. put on the market the now familiar Service rifle bored for the ;22 rim-fire cartridge. In 1904 the Birmingham Small Arms Company were manufacturing a similar weapon, and since that date it has been possible to get the successive types of Service rifle constructed to shoot the low-power cartridge.

During the present war very many thousands of recruits have had their first introduction to a Service rifle through the medium of these .22 Service weapons, and there is no doubt at all that as a quick introduction to the full-charge weapon nothing can equal the same pattern barrelled and bored to take the miniature cartridge. A man can be taught to shoot with any rifle, and if he only goes far enough it will not subsequently matter what class of rifle he takes up he will be quite at home with it within a few minutes. But when a man has to be taught quickly to shoot, there is nothinglike letting him stick to the type of weapon he is to use.

The first Miniature Rifle Prize meeting held in Great Britain took place at the Crystal Palace from March 23 to April I, 1903. The meeting was opened by General Sir Ian Hamilton, supported by Earl Grey. The programme included twenty-five competitions, thirteen for individuals and eleven for teams. For the prizes over one thousand nine hundred and seventy-one competitors entered, representing forty-eight rifle: clubs. The shooting was conducted at two ranges, the shortest being 20 yards and the longest 50 yards. The targets were adaptations of the N.R.A. dimensions. The bull's-eye at. 20 yards was a black of 7/8 in. diameter scoring five masks, with a central ring scoring six marks. The inner was a in. in diameter, and the rest of the 6-in. square target counted as the outer. At 50 yards the black scoring five was 1-3/4 in. in diameter. At this range there was also the central, counting six. The 50 yards target was It in. square. The standing position was adopted for the to yards range, the prone position for the 50 yards range. This rule applied to all competitions except the Championship, where shots were fired both standing, kneeling, and prone at both ranges.

One of the chief results of this meeting was the prominence which it gave to the unreliable character of shooting from the Morris tube. So unsatisfactory were the results obtained that it was determined at future meetings held by the Society of Working Men's Rifle Clubs a separate class would have to be-made for it as it was quite unfit, except in specially lucky circumstances, to compete against the much cheaper and less complicated Belgian and American rifles made to fire the .22 cartridges .

The shooting at this meeting was nothing like the class which we have now learned to expect of the miniature rifle, but it must be remembered that aperture sights and orthoptic spectacles were not permitted, and both rifles and ammunition were in an undeveloped state. The champion- ship was won by the well-known Service rifle-shot, A. J. Comber.

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

Extract from "Random Writings on Rifle Shooting" by A.G. Banks (1934) referring to competitions held in 1908.

Judged by our present standards, the shooting was amazingly bad. The championship of the Manchester meeting in 1908 was won with a score of 385 (" through the ranges," plus a " rapid " at 50). Top score in the winning International team at the same meeting was 291! But such shooting was not considered bad then, and, looking back, I have grave doubts whether our ammunition could be guaranteed to hold the one-inch carton at 50 yards, or even the half-inch one at 25 with certainty.

Meetings in those happy days were certainly carried out in a more free-and-easy and less desperately serious manner than they are to-day, when you know perfectly well that even though you make 300 through the ranges in a competition, you are more than likely to tie with two or three others and get counted out on the gauges, or the dotted line! I remember seeing fellows then, after shooting black-powder ammunition, sitting about on the firing points pulling-through their barrels between shoots. (The pull-through was a much used weapon of barrel-destruction in those days.)

The first Sharpshooter competitions were carried out at pot eggs at 100 yards, instead of the breakable discs which soon supplanted them. Those eggs, with rifles and ammunition of such variability, were hit more by good luck than good marks-manship ; and the three-minute time-limit was often reached with some still standing. The same applied in slightly less degree to the 2-inch discs, and many a time I have seen teams vainly blazing away at a clinging fragment for minutes on end, the odds being heavily against any accurately fired shot ever hitting it, though a lucky fluke might.

Amazing things sometimes happened, owing to this element of luck, the existence.of which we hardly realised at the time. Thus in a Skirmisher competition (at 50 yards, as now) I find the following note: " Won with a record score of 14 hits by the Southport team, consisting of three men only, to their opponents' four," It was a great battle, I remember, but would be an utterly impossible result to-day, when every accurately fired shot is sure of " getting there," and teams sometimes get 14 hits from one of their four members. It is, of course, no longer permissible to enter these competitions a man short, the authorities very rightly regarding such stunts as a waste of their time, under modern conditions.

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

Where might the small-bore rifle have fitted into the British, Commonwealth and allied Service rifle scene if the second World War had continued? Well, such rifles had already been issued to personnel who had been chosen as would-be members of the British resistance in the event of a succesful German invasion. These home-guard "guerrilla" style resistance units were intended to create havoc amongst a German occupying force by selecting important targets and eliminating them with a significant degree of stealth. DeLisle even designed and prototyped a small-bore version of his silenced SMLE based commando carbine for the British Special Forces. Additionally, some rifles issued at home are believed to have perhaps been .22RF versions of the No.4T sniper rifle. Such rifles do exist, and were used Post-War for sniper training and stored at Warminster. Their whereabouts now are unknown - unless you know better?

Such use of small-bore rifles has even been considered for jungle type arenas. Their light weight, comparative silence ( almost complete when moderated ) and great accuracy at short range were ideal qualifications where stealth was required. An article was written on the subject relating an interview with

Brigadier-General Merritt Edson (of the U.S. Marine Corps) in "The Rifleman", journal of the Society of Miniature Rifle Clubs, as it was at the time.

We copy the article below. It must be taken into consideration, in these politically correct times, that what is said must be taken in the context of the period. Immediately post the second World War, there was much to consider from the recent past and more to be taken into consideration for the future. The World was still not perceived as an entirely peaceful place, and the possibilty of further conflict was still very much in the mind of those whose duty it would be to deal with any new threat. Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

'Scope Sights on .22 and Value of Marksmanship

TELESCOPE SIGHTS

" The outstanding troops on Tarawa were our scout-sniper platoons. These were made up of expert riflemen, expert scouts, working in carefully organized, carefully trained teams. They were armed with Marine sniper rifles ; Springfields, with telescope sights. Those scopes might surprise you. Lots of them were long, target-type, eight-power instruments, with wide fields. Some were hunting scopes. In either case they were damned effective ! Those boys didn't waste a lot of ammunition ; they held and squeezed. When they fired, Jap rifles stopped cracking. That's better, even, than scoring a V-on the range ! But scoring Vs on the range is the way to learn to do it!: " There has been a lot of discussion, pro and con, about our carbine. In my opinion it's a good weapon for the use for which it is intended. It can't replace the rifle ; it hasn't the long-range accuracy,'nor the penetration. But it's fast handling, and it will get a bullet into a Jap in a hurry, at close ranges. That counts, in close fighting." I don't think much of the carbine as an officer's weapon. I don't think an officer needs a weapon, other than a strictly self-defence weapon. His job is to command. When he starts showing the boys how well he can shoot, his efficiency as a commander suffers.

" I'd say, arm officers with pistols. Other men whose basic weapon is not the rifle might better be armed with pistols, too ; such men as machine gunners. A machine gunner has a load to carry. Sling a rifle or a carbine over his shoulder and it handicaps him in the transportation and handling of his basic weapon. When the going gets tough he's apt to discard that extra burden. The pistol isn't in his way, yet it's there when he needs it. It would be even better if the pistol were carried in a Shoulder holster. You get in pretty deep sometimes in the jungle ; it's good to have your equipment high up on your person. Ay and out of the way. "Any weapon that will kill that fits a specific need is valuable. I can see plenty of places where the .22 calibre rifle could be used very effectively in jungle fighting, as a sniper's weapon. Ranges aren't apt to be long, in the jungle, and for those ranges the .22 scope-sighted would be superlatively accurate. It makes little flash, little noise. A sniper armed with it would be hard to locate. And it would do the job. I've heard, unofficially, that one of my junior officers killed a Jap on Tulagi with a Colt Woodsman. It doesn't surprise me in the least."

COMBAT ESSENTIALS

"The Jap, he's no superman by any means. He's no better woodsman than our men, except when he's been trained longer ; and he isn't even potentially as good a rifleman.

" That's bad- for him, because the individual rifleman is the back- bone of every army. Everything else - the tanks, the planes, the artillery, even the Navy - are supporting arms to back up or pave the way for the man with the rifle : the man who goes in on his own two feet, to take and hold the ground.

" It is rifle fire that ultimately takes ground, and it is rifle fire that holds it after it's taken, by throwing back enemy counter-attack. The man with the rifle is the man who wins wars ; and accurate fire from individual riflemen is the most effective factor on any battlefield. We've proved that, on Guadalcanal, at 'the Ridge', at Tulagi, at Tarawa, and everywhere we've gone into action, in this war and in wars past.

., " Lots of people have wrong ideas about training men for combat shooting. They stress fire power above accuracy, and they look for some

short cut by which they teach men to be good combat shooters without teaching them the good old fundamentals of basic marksmanship - to hold and squeeze and hit targets at known ranges. In my .opinion that's wrong. Fire power is important, but it is effective only in so far as it is accurate - and the more accurate it is, the less fire that's needed. Teach basic marksmanship first. Given that, a man can devote his whole mind to the meeting of combat conditions without being in doubt of his ability to kill his enemy, once the enemy is met.

" Teach target marksmanship at known ranges first. Then teach the man to estimate his own ranges. Teach him to shoot at indistict targets , at moving targets . Teach him to scout: to take cover properly, to move properly, to use his eyes to see before being seen. Teach him then to work as a part of a team : to support his teammates and to make use of the support they give him. But, above all else, give him a knowledge of and a confidence in his weapon and in his ability to use it ! Given that, he'll learn the other things quickly. Lacking that, a man goes into battle mentally unarmed. His weapons are small comfort to him because he has no faith in them.He is handicapped, because he isn't sure what he can do when he meets the enemy. Give him confidence in his gun and his ability to use it, and he can devote his efforts to taking care of himself and making contact with the enemy, knowing that when that contact is made, he can make the most of it.

"Too, having faith in his weapons, a man will take care of those weapons. Lacking faith in them, he takes poor care of them, with the frequent result that they don't function properly when he needs them. We saw plenty of that in the Islands. Mud and salt water and coral sand don't improve automatic and semi-automatic weapons, and unless a man loves and trusts his weapons, when he's dog-weary he's apt not to. bother to clean them. Give him supreme confidence in that gun as the thing that will stand between him and death, and he'll clean it ! He'll clean it first, and worry less about his own ills for having done it.

" Teach him to shoot before he ever goes into the service. Teach him to shoot again, after he's in. Teach him to shoot, again and again, every chance you get. Give him refresher courses. ' Frequent application of the seat of the man to the seat of the saddle' is a good way to make a rider ; frequent practice is the only way to make a good shooter. Teach men to correct errors made in battle by means of target-range practice, and pretty soon they'll be using target-range skills in battle. Once you get them doing that, you've got an army !"And finally, we copy a letter, following the interview recorded in "The Rifleman", written by Major-General Julian C. Smith, from the Office of the Commanding General, Fleet Marine Forces (U.S.), Pacific, and originally addressed to the "American Rifleman"

"THE SCORE IS THE PROOF"

Office of the Commanding General,

Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific.

Editor,

I was talking to Colonel Murray, who commanded a battalion of the Sixth Marines at Tarawa and Saipan. He also fought at Guadalcanal, and was wounded at Saipan. I asked him what training he would stress for his battalion to prepare it for the next battle. We have so many weapons in an infantry battalion nowadays that I was really curious to get his reaction.

He said," I would spend more time teaching them rifle marksmanship than anything else."

He found that Japs were very good shots at short, range. He also found that automatic weapons, such as machine guns and BAR'S,

often fail to hit individuals at 250 yards and beyond, whereas his good rifle shots could pick them off. He said, "I would like to have my

men all able to pick off individual Japs at about a hundred yards farther than the Jap riflemen can pick us off."

Murray's battalion cleared up the remainder of Tarawa Atoll after Betio had been captured. The Japs all withdrew to the northern end

of the atoll and made a final stand. The ranges in the last steps of the attack were very short and the Japs, who were among the best

trained Japanese troops, were unexpectedly good shots. Quite a number of our men were shot through the head when they lifted their

heads looking for the enemy. Also, an amazingly large number were shot through the right arm or shoulder while in the act of throwing

grenades. However, the better shooting of the Marines showed up in the fact that they buried 156 .Japs, with the loss of about 80 of his own

men killed and wounded.

Major-General JULIAN C. SMITH.

The whole article finished with an advertisement for a new publication.

A new book. Rifle Shooting for Cadets, by Lieut.-Colonel E. R. Godfrey, is published by Messrs. Gale and Polden Ltd. at Is. 8d. post free.

" That every boy in the Empire for the next hundred years should be a marksman is a form of national insurance we dare not neglect,"

says Colonel Godfrey. He deals with many individual problems in a way both practicaland interesting.

We make no apology for including these, only partially relevant, passages in this page allotted to the British small-bore training carbines of the period. Please draw your own inferences and conclusions. It is not our wish to put words into the mouths of others.

Return to: SITE MAP or MENU PAGE or TOP of PAGE

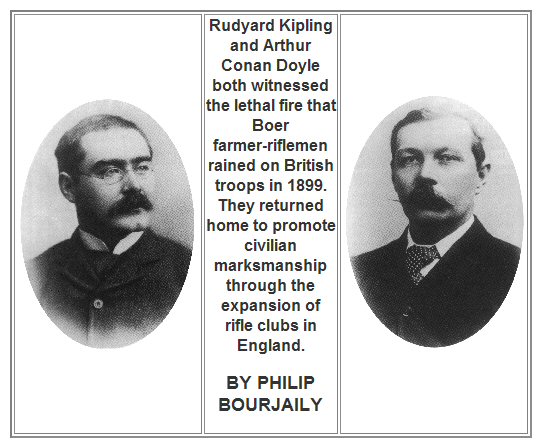

This article originally appeared in the June 1989 edition

of the American RIFLEMAN

and is here reproduced with their, and the author's, kind permission.

Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Conan Doyle both witnessed the lethal fire that Boer farmer-riflemen rained on British troops in 1899. They returned home to promote civilian marksmanship through the expansion of rifle clubs in England.

BY PHILIP BOURJAILY THE civilian rifle club movement in England grew out of the disasters of the first months of the Anglo-Boer War late in 1899. The British Army suffered a series of reverses at the hands of outnumbered civilians unlike anything the nation had witnessed in the prior years. One of the shocking revelations of the war was the poor standard of marksmanship in the army compared to that of the Boers. The Boers grew up hunting and riding; each burgher provided his own horse and rifle when he joined his commando. These expert game shots, partial to the bolt-action Mauser repeater, took a heavy toll on British troops often ordered to advance in long lines as if fighting lightly armed tribesmen.

Two men who would later found rifle clubs early in the movement were among the many who followed the course of the war with great anxiety: Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Conan Doyle.

Kipling, the poet laureate of the British Army, was appalled to read in the papers how the regulars he had glorified in his stories and poems were mauled repeatedly by a handful of farmers. He tried to help on the home front, first by a failed attempt to start a volunteer company in the resort town of Rottingdean where he lived, then by writing ``The Absent Minded Beggar."

The poem was critically reviled but extremely successful in its purpose of raising money for the wives and families of soldiers serving in South Africa. Finally on Jan. 20, 1900, Rudyard Kipling left for Cape Town to see the situation firsthand.

Sherlock Holmes creator Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle had been turned down by the Middlesex Yeomanry when he applied for a commission early in the war, but he was subsequently offered a position on the staff of a private field hospital due to leave for the front in the spring of 1900. In the intervening months, Conan Doyle experimented with an idea: since the Boers often fought from trenches, why not drop bullets on their heads via "high angle" rifle fire? Conan Doyle made and tested a prototype high angle sight and wrote several letters to the War Office promoting his idea, which was rejected as impractical.

The tide of the war had already turned in favor of the British when Conan Doyle arrived at Lord Roberts` headquarters in the city of Bloemfontein on April 2, 1900. Kipling, who had just spent six weeks working on the staff of the military newspaper The Bloemfontein Friend, returned to Cape Town on April 3. Although the two authors were mutual admirers and casual friends--Conan Doyle had been a house guest of the Kiplings in Vermont in 1894--apparently they just missed one another in South Africa.

Dr. Conan Doyle and the staff of the Langman Hospital were soon swamped by a massive outbreak of typhoid fever among the troops after the Boers cut off the city`s fresh water supply. Nevertheless, Conan Doyle found time to go briefly into combat with the army during its advance on the town of Brandfort. He was as impressed with the scale of the modern battlefield and the range of the weapons as Kipling had been when he witnessed the battle of Karee Siding in March. At one point during the fighting, Kipling wrote: ". . . (we) move(d) forward to the lip of a large hollow where sheep were grazing. Some of them began to drop and kick. `That`s both sides trying sighting shots` said my companion. `What range do you make it?` I asked. `Eight hundred at the nearest. That`s close quarters nowadays. You`ll never see anything closer. Modern rifles make it impossible. ` ``

Although the Boer War offered firsthand proof to the British that accurate rifles had changed the nature of warfare, a tremendous enthusiasm had surrounded the rifle since the authorization of the volunteer rifle companies in 1859. The volunteers, a Victorian fad for amateur soldiering, were popularized by periodic rumors of a French ironclad battle fleet. The National Rifle Association of Great Britain was founded in 1859 as well, to promote a national taste for rifle shooting and thereby sustain interest among the volunteers between invasion scares. The association`s stated aim was to make the rifle "what the bow was in the days of the Plantagenets"--a national weapon. For the history-conscious Victorians, the parallels between the rifle, a weapon requiring far more skill and practice than the smoothbore musket it replaced, and the longbow, were irresistible.

Queen Victoria, whose reign stretched into the Boer War, fired the opening shot at the British NRA`s first meeting at Wimbledon on July 1, 1860. The British NRA`s birth preceded the American NRA`s by 12 years.

"What the `clothyard shaft and grey goose-wing` effected, when guided by an English eye and an English hand at Crecy and Agincourt, the rifle bullet will do in any future contest...." wrote Hans Busk in The Rifle and How to Use it.

The London Times went so far as to editorialize: "The change from the old musket to the modern rifle has acted on the very life of the nation, like the changes from acorn to wheat and stone to iron are said to have revolutionized the primitive races of men."

Despite the NRA`s best efforts during the previous 40 years, the war in South Africa demonstrated clearly that England was not yet a nation of marksmen. In May 1900 Prime Minister Lord Salisbury called for the formation of civilian rifle clubs to redress the shortcoming. In a speech to the Primrose League, he stated his goal was no less than that "a rifle should be kept in every cottage in the land." In response the NRA formulated its guidelines for the affiliation of civilian clubs. Ninety-two were formed that first year, among them Rudyard Kipling`s club at Rottingdean and Arthur Conan Doyle`s Undershaw Rifle Club.

Kipling had returned home to Rottingdean convinced that the English people had grown too soft and complacent to defend their empire. Not only had the regular army had a difficult time with the Boers, it had compared poorly to its colonial allies; the Australians and New Zealanders had adapted easily to the irregular warfare of their opponents. Kipling was then at the height of his fame and popularity, and he was determined to use his status as a platform for moral leadership, both through his writing, and in the summer of 1900, by example.

The first task facing Kipling as he started the rifle club was in many ways the most difficult: securing space for a 1000-yd. range. On a small island nation such space was at a premium; even the royally supported NRA had been forced to move its annual meeting from Wimbledon to Bisley when stray bullets began striking the Duke of Cambridge`s property. Nothing less than a full-size range would do for Kipling, however, and in July he was able to write to his American friend Dr. James Conland: "... the bulk of my efforts have been in trying to get a rifle range over these open downs. At last I think I have succeeded and after untold bothers the landowners have given their consent to our putting up targets and butts. It was a weary business corresponding with lawyers and land-agents and generally making oneself agreeable to everyone--but now [that] we have started a village rifle club I begin to see a reward for my labors."

It was not the Boer War that motivated Kipling but the continental war with Germany that he already foresaw. He threw himself into club activities, serving as president, personally paying for new targets to replace the old windmill type, presenting the club with a Nordenfeldt gun that had been used in South Africa and taking his turn as musketry instructor, familiarizing club members with the .303 Enfield service rifle. ". . . my real work this summer has been connected with our new rifle range," he wrote to Dr. Conland in December. "The men are just as keen as can be and turn up every week to put in their firing. Can you imagine me in corduroy clothes and a squash hat with the Club ribbon around it in charge of a firing party of four on the ground; an hour of standing over the rifles with one eye on the targets and the other on the men (Some of `em have queer notions about shooting)."

President Kipling oversaw the construction of a drill shed for winter training. Although Kipling spent the winter of 1900- 01 in Cape Town, the instructions he left behind testify to his seriousness about the club`s activities:

Instructions for the use of shed during my absence:Men to have two evenings a week for MT (Morris Tube) practice and such other evenings as the Sergeant shall see fit for

Gardner Gun Drill

Signalling

Guard Drill, etc.

Boys to have two evenings a week. One for MT practice and one for gymnastics.

Boys evenings are not to be Monday and Wednesday.

Men and Boys evenings to be kept separate.

Men to be instructed in gym work if Sergeant thinks fit.

Fatigue parties must be told off to clear up the shed, every night as there will be no allowance for caretakers.

All damage must be paid for by offender.

The Rifle Club may hold meetings and concerts in the shed under Sergeant`s supervision. No intoxicating drinks under any circumstances.

Smoking is permitted.

Cst. Gd. Wells is to be in charge of the Gardner Gun with right of way and free entry into shed for that purpose.

Rudyard KiplingArthur Conan Doyle drew a different lesson from the Boer War than did Rudyard Kipling. Recognizing the English peoples` aversion to conscription, and opposed to compulsory service himself, Conan Doyle saw the war as proof that civilian marksmen could effectively resist invasion. He founded the Undershaw Rifle Club and explained his purpose in a letter to the Glasgow Evening News entitled ``Burghers of the Queen" in December of 1900. Conan Doyle wrote: ". . . the idea I am working with is simply riflemen drawn from the resident civilians. The men are quite eager to pay for their own cartridges which, with the Morris Tube system, can be sold at three for a penny. I made ranges for them at 50, 75 and 100 yds., the latter representing 600 yds. without the Morris Tube system . . . on Holidays I will give them a prize to shoot for . . . the whole expense of targets (5), mantlets, rifles (3), with tubes is not more than £30.``

For the pragmatically minded Conan Doyle, the "miniature`` or .22 rimfire smallbore range seemed a more practical solution to the problem of space than a full-size 1000-yd. range like the one at Rottingdean. (The Morris Tube was a barrel insert for the service rifle that allowed it to chamber the .297/.230 short or long, a center-fire equivalent of the .22 rimfire.)

"Miniature Club" .22 rimfire or .297/.230 center-fire rifles were favored by Arthur Conan Doyle for marksmanship training because the requirements for ranges were more easily met than for large bores.

Conan Doyle further proposed that all men between the ages of 16 and 60 (not coincidentally the age limits for Boer soldiers) should train in rifle clubs. Those reaching a certain level of proficiency would be awarded a distinctive broad-brimmed hat and a rifle and bandolier to keep at home, a "uniform" remarkably like that worn by the Boers.

When the military correspondent for the Westminster Gazetteer criticized his ideas, Conan Doyle responded: "I have stood all day today marking for our own corps of civilian riflemen. Gentlemen, shopboys, cabmen, carters and peasants were all shooting side by side. The prize, at a range which was equivalent to 600 yds., was taken by a top score of 83 out of 90; 82, 81 and 80 were next. Fifty men spent their bank holiday at my butts, and the scene was like a village competition in Switzerland. Conceive the stupidity that would refuse military material such as that when all it will ever ask of its country is a rifle and a bandolier!"

By January 1901, Conan Doyle was ready to pronounce the club a success, and he wrote to the local paper, the Farnham, Haslemere and Hindhead Gazette: "I hope to see similar clubs started at Headley, Churt, Tilford, Witley, Chiddingfold and especially at Haslemere. If any gentleman desires to organize one, and so help in what is a very urgent public duty, I will be happy to furnish him with full information as to the methods by which we have brought our own success. "

At the end of that summer, Kipling also had reason to be pleased with the results of his work. He wrote again to Dr. Conland: ". . . the end of the season shows we have forty very fair shots and about thirty men who at least know something of shooting. We`ve won every match so far (six in all) that we`ve shot against outside teams; and some of the teams were fairly strong ones.``

Unfortunately, we have no better account of Kipling`s marksmanship other than that he shot "adequately" despite his poor eyesight and that he scored a bullseye at the opening ceremonies of the Winchester Drill Hall. He was, however, a fierce competitor, shooting in all of the club`s matches, serious to the point of surliness. When a member of the visiting Newhaven Volunteers expressed his interest in meeting the great man at a match in Rottingdean, Kipling snapped "Well, now you can see the animal on his own ground."

Kipling eschewed special treatment, insisting that everyone must "muck in together" in the important business of preparing for war. Unfortunately his celebrity drove him away from the resort town of Rottingdean and the rifle club. Curious sightseers continuously invaded his privacy, and a local tour bus line made his house one of its most popular stops. Late in the summer of 1902, the Kiplings moved to a house in the country. The Islanders was published shortly thereafter. In the scathingly sarcastic poem, Kipling made plain his scorn for the English people he felt would rather play games than prepare for war, and ridiculed the Duke of Wellington`s notion that wars were won on the playing fields of Eton:

Will ye pitch some white pavillion and lustily even the odds

With nets and hoops and mallets, with rackets and bats and rods?

Will the rabbit war with your foeman-- the red deer horn him for hire?

Your kept cock pheasant keep you-- he is master of many a shire

Arid, aloof, incurious, unthinking, unthanking, gelt

Will ye loose your schools to flout them, till their brow beat columns melt?

Kipling`s proposed solution was simple and true to form:

Each man born to the Island, broke to the matter of war

Soberly and by custom taken and trained for the same

Each man born to the Island entered at youth to the game