Whitworth trials rifle in .451-inch calibre

One of two made by B.S.A. for a Turkish contract

The following note was written by the late William (Bill) Curtis, A.C.I.I., then Assistant Curator of the National Rifle Association's Museum collection at Bisley, Surrey. Vice President (Hon.), Crimean War Research Society, (Hon. Life), Whitworth Rifle Research Project, MLAGB*.

(*The Muzzle-Loading Association of Great Britain)

"BSA & Co. were awarded a contract ca. 1865 to supply .577 Pattern 1861 Short Rifles to the Turkish Government (the Porte). These were signed on the lock plate with the Sultan's Tughra, and marked BSA and the date. Two trial rifles matching these but in .451 Whitworth hexagonal bore were also noted, apparently an effort to attract a contract for Whitworths. Whitworth in fact sold off the small arms side of his business to BSA in 1865."

Illustrated is the one of the two rifles described above.

Both rifles were manufactured by the Birmingham Small Arms Company

Drag horizontally to rotate subject - Click to zoom and drag to pan - Full screen viewing from expansion arrows.

The Tughra engraved on the lock is recorded as being that of the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid I (born 1823 - died 1861. His son, Abdülhamid II, (born 1842 - died 1909), did not become sultan until 1876. The Tughras of each were very similar, with an almost identical main icon, but that of the son had two small icons added, one either side.

Abdülhamid I

The Tughra is engraved on the lock plate below the percussion nipple,

and behind the hammer fulchrum is the mark

BSA & Co.

1865

The barrel's tangent rear-sight - calibrated in 100 yard increments to 1,000 yards.

The hammer drawn back to half-cock, showing the nipple for the percussion cap.

The barrel is simply engraved "WHITWORTH PATENT".

Below: the muzzle, with a heavily chamferred crown, shows the six-grooved bore,

deeply cut for the hexagonal Whitworth bullet.

The barrel band, with its sling-swivel, is profiled to receive the ram-rod for loading and cleaning.

An inspection mark is just visible on the fore-end cap.

Below: the barrel's proof marks - dated for 1852,

and the simply engraved "WHITWORTH PATENT".

Next, an image of the bore at the muzzle.

And two more of 40 images stacked to show the full length of the bore;

one from a metre away ........

...... and the other from close up, slightly offset to better show the rifling.

N.B. The table has yet to be completed

DATA TABLE - ALL MEASUREMENTS AS VIEWED |

||

FIREARM |

IMPERIAL |

METRIC |

| Designation or Type : | Military Pattern Rifle |

- |

| Action Type : | Percussion |

- |

| Nomenclature : | Whitworth trials |

No serial nuo. |

| Calibre : | .451 inch |

- |

| Weight : | lbs. ozs. |

kgs |

| Length - Overall : | inches |

cms |

| Length - Barrel : | inches |

cms |

| Pull : | inches |

cms |

| Furniture : | Walnut |

- |

Rifling - No./Type of Grooves : |

6 - hexagonal cut |

- |

| Rifling - Twist : | 1 turn in ? inches - RH |

1 : ? cms |

| Rifling - Groove width : | inches |

mm |

| Rifling - Land width : | inches |

mm |

Rifling - Groove depth at muzzle : |

inches |

mm |

| Sight - Fore : | - |

|

| Sight - Rear : | - |

|

| Sight - Radius : | inches |

cms |

In 1861, in the "Class Book for the School of Musketry" at Hythe, Kent,

Colonel E. C. Wilford, then Assistant-Commandant and Chief Instructor,

wrote the following relating to Whitwoth.

Almost every conceivable form of projectile, internal and external, have been made and experimented upon. Auxiliaries to expansion have been used, made of metal, horn-wood, and leather, with plugs, screws, or cups divers shapes. Cannelures are used, of varying forms, depth and number. It has even been attempted to construct bullets upon the screw principle, so that the projectile should receive spirality from the action of the air upon its outer or inner surface, when fired out of a smooth bore musket.

The general characteristics of the European rifles, up to 1850, are a very large calibre, a comparatively light short barrel, with a quick twist, i.e., about one turn in three feet, sometimes using a patch, and sometimes not, the bullet circular, and its front part flattened by starting and ramming down.

It appears that the introduction of additional weight in the barrel, reduction in the size of the calibre, the constant use of the patch, a slower twist, generally one turn in 6ft., combined with (what is now known to be a detriment) great length of barrel, are exclusively American.

A round ended picket (plate 20, fig. 16), was occasionally used in some parts of the States, until the invention of Mr. Allen Clarke, of the flat ended picket, which allows a much greater charge of powder, producing greater velocity, and consequently less variation in a side wind.

A rifle may perform first rate at short ranges, and fail entirely at long, while a rifle which will fire well at extreme ranges can never fail of good shooting at short. In fact certain calibres, &c., &c., perform best at certain distances, and in the combinations of a perfect rifle there are certain points to be attended to, or the weapon will be deficient and inferior.

It is desirable to give a bullet as much velocity as it can safely be started with, and the limit is the recoil of the gun, and the liability of the bullets to be upset or destroyed, for as soon as this upsetting takes place, the performance becomes inferior, and the circle of error enlarged.

It is clear that a bullet projected with sufficient twist to keep it steady in boisterous and 'windy weather, must of necessity have more twist than is actually necessary in a still favourable time ; hence a rifle for general purposes, should always have too much twist rather than too little.

The weight of the bullet must be proportioned to the distance it is intended to be projected with the greatest accuracy; for it is a law, that with bodies of the same densities, small ones lose their momentum sooner than large ones. It would be madness to use a bullet ninety to the pound at nine hundred yards, merely because it performed first rate at two hundred yards; or a forty to the pound at two hundred yards, because it performed well at nine hundred yards. The reason is that a forty to the pound cannot be projected with as much velocity at two hundred yards, as the ninety to the pound can, because the ninety uses more powder in proportion to the weight of the bullet than the forty does. Again, the heavier bullet performs better than the lighter one at nine hundred yards, simply because the momentum of the light ball is nearly expended at so long a range as nine hundred yards, and its rotatory motion is not enough to keep it in the true line of its flight, whereas a heavy bullet, having from its weight more momentum, preserves for a longer distance the twist and velocity with which it started.

As weight of projectile is a leading element in obtaining accuracy at long ranges, and as the weight cannot be increased beyond a certain limit in small arm ammunition, hence a small bore is an indispensable requisite for a perfect rifle.

In the foregoing brief summary of the most important properties which should be possessed by a first class rifle, we have dealt in generalities, but we shall now record the experience of Mr. Whitworth, who has entered into the most minute details, and has pointed out the harmony which should subsist between the twist, bore, &c., and the projectile, in the combinations of a perfect rifle.

Premising, that when Mr. Whitworth was solicited by the late honored Lord Hardinge to render the aid of his mechanical genius to the improvement or perfecting a military weapon, he was restricted as to length of barrel, viz., 3 feet 3-in., and weight of bullet, .530 grains. We shall now proceed and use Mr. Whitworth's words.

" Having noticed the form (hexagonal) of the interior which provides the best " rifling surfaces, the next thing to be considered is the proper curve which rifled " barrels ought to possess, in order to give the projectile the necessary degree of " rotation."

With the hexagonal barrel, I use much quicker turn and can fire projectiles of any required length, as with the quickest that may be desirable they do not strip.

I made a short barrel with one turn in the inch (simply to try the effect of an extreme velocity of rotation) and found that I could fire from it mechanically-fitting projectiles made of an alloy of lead and tin, with a charge of 35 grains of powder they penetrated through seven inches of elm planks."

After many experiments, in order to determine the diameter for the bore and degree of spirality, Mr. -Whitworth adds :

"For an ordinary military barrel, 39 inches long, I proposed a .45-inch bore, with one turn in 20 inches, which is in my opinion the best for this length. The rotation is sufficient with a bullet of the requisite specific gravity, for a range of 2000 yards. Under these conditions the projectiles on leaving the gun would be about two and a half diameters of the bore in length. The gun responds to every increase of charge, by firing with lower elevation, from the service charge of 70 grains up to 120 grains ; this latter charge is the largest that can be effectively consumed, and the recoil then becomes more than the shoulder can conveniently bear with the weight of the service musket.

The advocates of the slow turn of one in 6 feet 6 inches, consider that a quick turn causes so much friction as to impede the progress of the ball to an injurious and sometimes dangerous degree, and to produce loss of elevation and range ; but my experiments show the contrary to be the case. The effect of too quick a turn, as to friction, is felt in the greatest degree when the projectile has attained its highest velocity in the barrel, that is at the muzzle, and is felt in the least degree when the projectile is beginning to move, at the breech. The great strain put upon a gun at the instant of explosion is due, not to the resistance of friction, but to the vis inertia of the projectile which has to be overcome. In a long barrel, with an extremely quick turn, the resistance offered to the progress of the projectile is very great at the muzzle, and although moderate charges give good results, the rifle will not respond to increased charges by giving a better elevation. If the barrel be cut shorter, an increase of charge then lowers the elevation.

The use of an increasing or varying turn is obviously injurious, for besides altering the shape of the bullet, it causes increased resistance at the muzzle, the very place where relief is wanted.

Finding that all difficulty arising from length of projectiles, is overcome bygiving sufficient rotation, and that any weight that may be necessary can be obtained by adding to the length, I adopted for the bullet of the service weight, an increased length, and a reduced diameter, and obtained a comparatively low trajectory; less elevation is required, and the path of the projectile lies more nearly in a straight line, making it more likely to hit any object of moderate height within range, and rendering mistakes in judging distances of less moment. The time of flight being shortened, the projectile is very much less deflected by the action of the wind.

It is most important to observe that with all expanding bullets proper powder must be employed. In many cases this kind of bullet has failed, owing to the use of a slowly igniting powder, which is desirable for a hard metal projectile, as it causes less strain upon the piece, but is unsuitable with a soft metal expanding projectile, for which a quickly igniting powder is absolutely requisite to insure a complete expansion, which will fill the bore. Unless this is done the gases rush past the bullet between it and the barrel, the latter becomes foul, the bullet is distorted, and the shooting must be bad. If the projectiles used be made of the same hexagonal shape externally as the bore of the barrel internally, that is, with a mechanical fit, metals of all degrees of hardness, from lead, or lead and tin, up to hardened steel may be employed, and slowly igniting powder, like that of the service may be employed."

Mr. Whitworth does not lay claim to any originality as inventor of the polygonal system, but merely brings it forward, as the most certain mode of securing spiral motion, but he deserves to be honored by all Riflemen, as having established the degree of spirality, the diameter of bore, to ensure the best results from a given weight of lead, and length of barrel.

CONCLUSION.

In achieving the important position obtained by the rifle in the present day, it has nevertheless effected no more than was predicted of it by Leutman, the Academician of St. Petersburg, in 1728, by Euler, Borda, and Gassencli, and by our eminent but hitherto forgotten countryman Robins, who in 1747, urgently called the attention of the Government and the public to the importance of this description of fire-arm as a military weapon.

In the War of American Independence, the rifle, there long established as the national arm for the chase, exhibited its superiority as a war arm also, in so sensible a manner, that we were constrained to oppose to the American hunters the subsidised Riflemen of Hesse, Hanover, and Denmark.

The Hythe book, from which this extract is taken,

also carries a comprehensive History of the Rifle written by Col. Wilford,

which can be found via the above link.

Worthy of mention is the opening of the new Wimbledon ranges by Queen Victoria,

as Patron for the National Rifle Association in 1860.

The Queen fired a Whitworth rifle from a fixed rest using a trigger lanyard.

The large cast iron target, at which Queen Victoria's first shot at Wimbledon was fired,

resides to this day in the N.R.A. Museum at Bisley Camp, Surrey ( U.K.),

to whence the N.R.A. was obliged to relocate thirty years later.

The target is shown below, with a small white arrow pointing to its central hit.

Below is a close-up image better showing the Whitworth bullet strike.

A newspaper reporting on the National Rifle Association of the U.S.A.

carried the following engraving contemporary to the opening

of the British NRA Wimbledon ranges by Queen Victoria,

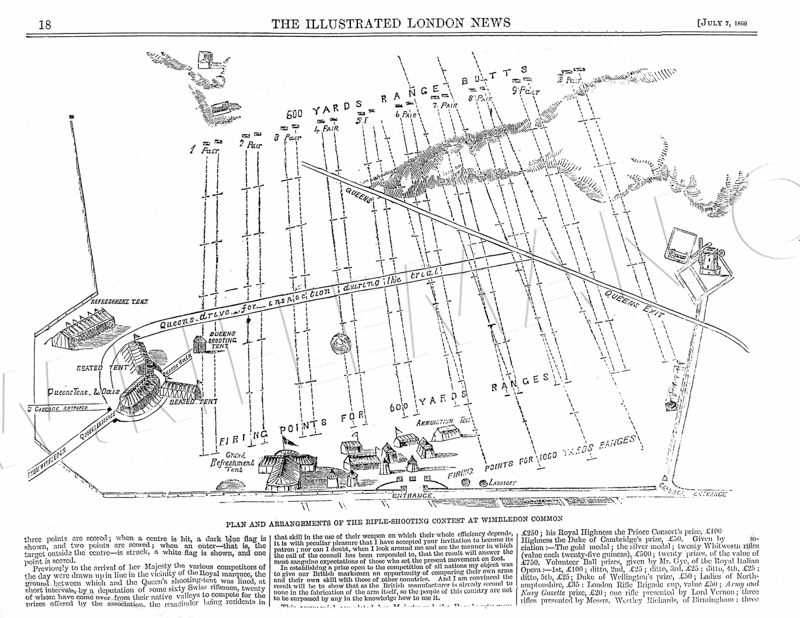

The London Illustrated News of July 1860 published a map of the Wimbledon Camp

showing the positions of the ranges, pavilions and the tent from which

Queen Victoria fired that famous first shot from the specially constructed aiming rest.

The occasion was celebrated by the makers of a well-known "Gentleman's Relish" paste,

by recording the event with a fine picture printed onto their ceramic pot lids.

Nowadays significant collector's items, the many different paintings produced

on these lids have often been framed for display as wallpieces.

In 1874, Wimbledon saw the introduction of the butts gallery canvas targetry system.

The current Bisley ranges galleries are little changed in design.